The classic nation state is about ‘one people and one country’. It often talks about linguistic and cultural unity, but there are also aspects of ethnicity and religion.

The classic nation state is about ‘one people and one country’. It often talks about linguistic and cultural unity, but there are also aspects of ethnicity and religion.

For example, Sweden is the country of the Swedes, a people with a specific ethnicity and language. In this case, it is also a Protestant religious affiliation, which has now been diluted. There is also a plethora of different free churches, as well as a tendency towards atheism and agnosticism. In addition, there is a strong cultural cohesion, with minor variations in the different regions.

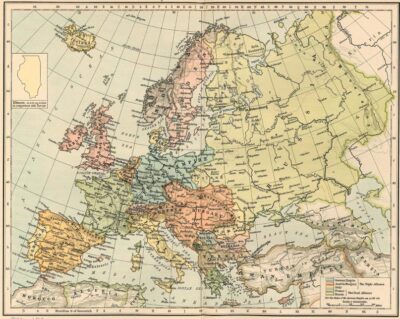

So what does it look like elsewhere in Europe? Here are some examples and challenges.

Equal but different

In the Southern Balkans, we have strong divisions despite linguistic unity, with Serbo-Croatian including various neighbouring dialects. Culture is also fairly similar, as is ethnicity; what differs is religion. We have Catholics in the west and Orthodox in the east, as well as some Muslim enclaves in the centre.

The Czech Republic and Slovakia went their separate ways even though they have similar language, culture and religion. There were also secession attempts in Catalonia and northern Italy, despite previous unity. Ukraine is also an example of related languages, but still deep divisions.

And also in the Nordic countries, with Swedes, Danes and Norwegians who understand each other, have the same origins, and similar culture and religion, yet have built separate nations.

Different but equal

And further opposite options with Switzerland, Belgium etc, showing that a nation can be made up of several different languages and ethnicities in a well-functioning unity. Even the United Kingdom is a union of peoples who previously had separate languages, which are still spoken in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Greek nation-building in the early 19th century included a large proportion of Albanians but also Slavs, who allied with the Greek-speaking population against the Ottomans. Greece was hardly homogeneous, even if it was fighting for a Greek nation state.

Could it be that (ancient) loyalties and alliances sometimes mattered more than language and ethnicity?

Old borders still apply

What we do realise is that Europe’s nation-building is not necessarily built on linguistic or cultural unity, despite our casual assumption that it is. We realise that deeper history plays a much bigger role.

Slovakia was part of Hungary during the Habsburg Empire, while the Czech Republic was under Austrian administration. Slovenia and Croatia were also part of the empire for a long time, but not Serbia. These old demarcations partly explain today’s division.

And Ukraine, by comparison, is a relatively new entity made up of different parts that used to belong to Poland, Austria-Hungary and Russia. Even today, we can draw borders along these regions, and there are differences in who they vote for in general elections, and where their general sympathies lie. Even though their dialects and origins are similar.

Building an empire

And then there is the current situation, where the European Union often trumps national parliaments. It is also a new kind of nation-building, we can call it an empire, as it consists of many different smaller states.

As we can see, the central power is obsessed with legislation concerning safety, standards and regulations. And that is quite normal for an empire, because its worst nightmare is disintegration, so you have to deal with this kind of control and regulation all the time. It is not of much use to the individual citizen, but it is of use to the empire.

The EU has been built quickly, and I do not think that citizens have kept up with the pace. In addition, we have huge immigration from other countries outside Europe. Soon our societies may resemble those of the Middle Ages, with different peoples living side by side under the same emperor (or sultan), and enclaves of people from still other areas. Different laws and rules may apply to the different groups, with ethnic religious leaders known as ethnarchs speaking for them to the overall state power.

In other words, there is little left of the old nation states of the 19th century. Perhaps they were just failed experiments? Or do they have a future if the European empire changes or falls?