Not so long ago, there was a powerful empire that stretched across the globe, from Europe, North America, Central America, Oceania, Asia, the Middle East to large parts of Africa. After the Second World War, the empire was divided up, and not much remained, at least according to the conventional explanation.

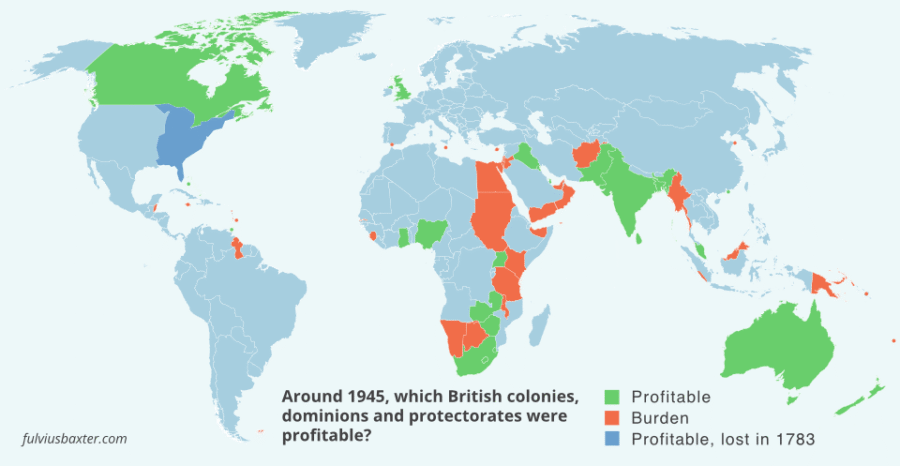

In these times of self-pitying post-colonialism, it may be interesting to look at the phenomenon from a more sober perspective. Firstly, we must realise that British colonialism did not come for free. Many colonies cost more than they delivered in tax revenues or private profits from British companies. Secondly, it sometimes required large investments in infrastructure, schools, hospitals, etc. Some of the colonies were at Stone Age level when they were incorporated into the empire, and the costs of developing them were extensive.

From a colonialist’s perspective, it is of course a matter of keeping the balance sheet healthy. Profitable colonies can finance continued expansion and pay for infrastructure investments in the new colonies until they too become profitable.

Of course, it is not quite that simple; profitability can fluctuate, and some colonies may never become profitable but are retained for strategic reasons. Sugar cane plantations in the Caribbean became unprofitable after the abolition of slavery and when sugar could be produced more efficiently. And British positions in Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus and Palestine were mainly geopolitical in origin and had no chance of becoming profitable.

India, which had long been the jewel in the crown, was of course profitable, as were Canada and Australia, which had a looser connection to the empire. The lost American states were also profitable, but they broke free at the end of the 18th century, and the empire had to partially rethink its strategy.

In 1945, the balance sheet was running a close race, with a remarkable number of colonies operating at a loss. In addition, England had large debts from the war, and the final nail in the coffin was probably India’s withdrawal in 1947. Without profitable India, it became difficult to support all the other less profitable areas. And note that several of the states on the Arabian Peninsula had not yet begun large-scale oil production and were still a loss-making business.

In the decades after the Second World War, the empire collapsed, the colonies became independent one by one, and the empire’s size was greatly reduced. Today, the British Commonwealth consists of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Plus a few smaller colonies scattered across the globe, totalling about 142 million subjects.

With a little goodwill, the remnants of the British Commonwealth can still be considered a superpower. Even though the territories have independent governments, they cooperate in a number of areas and have economic, cultural and military ties to each other. Add to this the good relations with the former colony of the United States, and one can still consider the ‘Anglosphere’ – perhaps not as a pure empire – but as an extremely strong power factor in the world, regardless of whether it is London or Washington that rules.