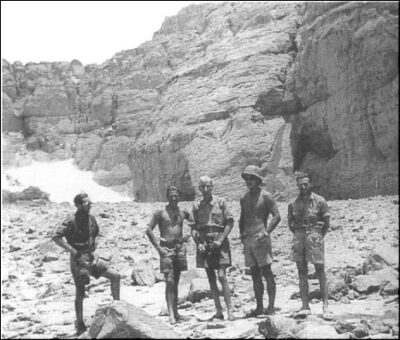

I read the notes of the famous aviator Almasy, twisting and turning the thumbed book, deciphered his intricate writing style with an even older Hungarian dictionary I had bought in an antiquarian bookshop. He had flown across the Sahara Desert, travelled where no one else had gone, seen things no one had seen before, one of the last great adventurers.

I read the notes of the famous aviator Almasy, twisting and turning the thumbed book, deciphered his intricate writing style with an even older Hungarian dictionary I had bought in an antiquarian bookshop. He had flown across the Sahara Desert, travelled where no one else had gone, seen things no one had seen before, one of the last great adventurers.

I envied the days when forgotten places could still be discovered, when expeditions were planned in smoky parlours, when big maps were unfolded and entries looked up in leather-bound dictionaries. We lived in different times now. The rational and soulless had taken over. Mysteries were fewer, and people were pale and bland.

Anyway, after spending many nights with that strange book, I thought I recognised a kind of pattern. Partly inspired by what I read, and partly by my long conversations with the Count.

There was something out there in the desert, something ancient and forgotten. Perhaps even the source of our civilisation, when the desert was once green and rivers flowed into the Mediterranean from the African continent. Before the ice melted, before people started to cultivate the land and settle, before the first cities were built. Then, when the early civilisations emerged, they seemed so complete even at an early stage, with amazing monuments allegedly built by people who had just taken the first step on the long staircase of cultural achievement.

I understood the Count and his companions’ reasoning about the ice ages. Yes, it would soon be colder again, our cycle was already complete and the millennial cold was soon to come. Although ‘soon’ in geological language could of course mean many years. But the realisation about climate was perhaps mostly a by-product of the other realisations, that somewhere west of Egypt there was once a people far superior to all others, whose empire was wiped out in the great upheaval of glacial retreat, followed by disasters, floods and later drought. The ruins were probably partly under water, or under layers of sediment and desert sand, far out of reach.

A few survived, made it to shore and became kings and leaders of the scattered nomadic tribes that populated the rest of the world. They were worshipped as gods, because their insights and knowledge led to great changes and great societies that would change human history forever.

I dismissed the idea that this mysterious people were described by some as unhuman, that they were not quite like us. It was too early to take that step. To settle for the idea of a bygone civilisation whose remnants enriched the rest of humanity was titillating and imaginative enough.

Now what was I to do with these insights? There wasn’t even anyone I could talk to. The Count was still gone. Many months had now passed, and he had not been heard from. Sometimes I wondered if he was even alive? He had bestowed some of his magic on me, sprinkled some of the animated substance, ignited my soul, and then left it to wither. But I was lucky to have known him. It was a great honour. Something I would never forget.

Soon I began to feel the inner turmoil, the clouds gathering, the air was charged, I had a slight headache. And the feeling that nothing would happen, that the world would go back to its usual hibernation if I didn’t take matters into my own hands and continue what so many had started before me.